Interviews

Exploring practitioner views on co-creation

In addition to the literature study on co-creation (read here), I have conducted 8 interviews with people that are dealing with co-creation in their profession. These practitioners offer interesting insights into the concept of co-creation, the benefits, success factors, risks and challenges.

I summarized the findings on this page, but you can download or view the complete article or view the Dutch article on Frankwatching.

A word of thanks

First and foremost I would like to thank the eight people that participated in the interviews for their enthusiasm, patience and active participation. They have been very willing to share their time and offer me insights in to their expertise and views. The interview with Tom de Ruyck was especially fruitful, since it resulted in a sponsorship for my MSc thesis experiment! I am glad with this confidence and looking forward to working with Insites Consulting

The Respondents

(full description of participants here)- Michael Blankert, Consumer Engagement Manager at PepsiCo

- Martijn van Kesteren, Consumer Insights Manager at Unilever

- Johan Sanders is Innovation Manager at Sara Lee

- Ingrid de Laat, Co-creation Consultant at the co-creation agency RedesignMe

- Ruurd Priester, Strategy Director at Lost Boys International (LBi)

- Tom de Ruyck, Sr. R&D Manager at Insites Consulting

- Johannes Gebauer, Team Manager of the HYVE Innovation Community

- Prof. dr. Will Reijnders, professor and director of the Executive Master of Marketing at TiasNimbas Business School

Page contents:

- The role of co-creation (Jump to)

- Benefits from co-creation (Jump to)

- Visions on success factors (Jump to)

- Challenges and misunderstandings (Jump to)

- Summarized overview (Jump to)

I The role of co-creation

The concept of co-creation

Participants agree that ‘co-creation’ is a bit of a buzz word that gets connected to a range of projects where consumers are -to different extents- involved in product innovation. De Ruyck distinguishes between two categories of co-creation; co-creation in the narrow sense and co-creation in the broad sense. In the narrow sense it concerns close collaboration between firms and consumers to generate new product ideas. In the broad sense co-creation comprises only specific aspects of product development or innovation processes. “The latter is what we do quite a lot, and it is often aimed at product improvement, such as packaging,” De Ruyck explains.

Van Kesteren sees co-creation in the purest sense as a collaboration between consumers and companies aimed at addressing relevant needs. However, he argues, some companies place too much responsibility on consumers. Van Kesteren: “You should not expect consumers to independently come up with an innovative and relevant solution.” He stresses co-creation should always be a joint collaboration and companies should provide relevant inputs and concepts, such that consumers can effectively respond to this.

Gebauer says: “If there is no authenticity and selling is the main goal of the firm, consumers will sense this and the co-creation will fail.”

A changing landscape

Nowadays, information about brands and firms has to be transparent, participants agree. Firms need to be able to justify whatever they claim in order to convince consumers and win their trust. The modern and savvy online consumers scrutinize information in search of evidence that convinces them in their beliefs. There is a general awareness that when firms don’t live up to their promises or to consumer expectations, there is risk of being criticized in the mass media. Gebauer notes that consumers are also more personally engaged in brands and products. “Consumers are now suddenly in charge and consider brands and products as ‘their own’ property, to state it provocatively,” Gebauer says.

Priester underlines the importance of connected online networks in today’s society: “(…) you end up in a network of consumers and producers. By means of co-creation you jointly generate value. You can use the network to test ideas and to show what the firm is doing.”

Reijnders has high expectations of the future role of co-creation, although he notes that in practice changes happen quite slowly and a lot still needs to happen. “Firms are in general still quite process- and product oriented,” he notes.

Firms have to focus on creating a more long-term competitive advantage by being consumer-centric and providing the best service and experiences. “New routes have to be developed to get closer to the consumer, and co-creation is one of these routes,” Reijnders argues.

II Benefits from co-creation

Firm related benefits

Participants agree that when co-creation is applied successfully, it can have different positive effects such as cost reduction and increased efficiency. In addition, interacting with involved consumers can inspire the internal team and enhance creativity.

Blankert: “Involving consumers generates a richness of ideas: the winning flavor in our Maak de Smaak campaign, Patatje Joppie, was something we would never have come up with ourselves.”

Van Kesteren notes that a long-term collaboration, e.g. via an online consumer community, offers more iteration possibilities. “It feels like having a direct ‘lifeline’ with consumers, you can ask questions instantly,” Van Kesteren says.

Priester: “You return to the core of added value; consumer value and experience. You reduce costs by having a direct dialogue with consumers (…) and create a more ‘lean and mean’ organization.” When firms succeed in developing more relevant products, this creates a ‘pull’ market and firms can reduce marketing budgets, Priester argues.

Sanders explains co-creation also positively affects the innovation process: “You work according to a tight schedule with predetermined deadlines and this makes the innovation process more tangible,” he argues.

Consumer related benefits

Throughout the interviews it is pointed out that consumers in turn also benefit from co-creation. Their involvement allows them to develop a positive relationship with the company, and they can influence product development by directly communicating needs and evaluating ideas. Besides that, co-creation is also a fun activity: “consumers feel in charge and empowered, which results in a feeling of joy,” as Gebauer states.

In the case of RedesignMe co-creators can also be professionals, and they can benefit by working flexible hours and earning money for their contributions. De Laat: “Our community offers beginning designers and marketers the opportunity to gain experience and to demonstrate their skills.” Practicing creative skills and gaining experience can be beneficial to consumers’ personal or professional development.

Product and brand related benefits

By constantly interacting with their target group firms use up-to-date information throughout the innovation process. All participants agree that co-creation, when done adequately, will result in relevant new products, which are better suited to future needs. “It is no longer about products, but about creating a superior experience,” Priester argues. “It requires exactly knowing in what way you can be relevant to the consumer,” he adds.

Participants agree that new, co-created products can positively influence existing brand perceptions, and create a more open and empathic brand image. Furthermore, satisfactory collaborations can turn co-creators into ‘brand ambassadors,’ promoting and talking about the brand with friends and peers.

Priester: “Consumers feel more involved with the firm, are better able to identify themselves with the brand and have the feeling their feedback is taken seriously.”

Blankert: “By means of co-creation you can get closer to consumers, (…) consumers will feel more connected to your brand.”

Sales effects

“Co-creation can be used to draw extra attention to a product introduction,” Sanders says. Due to this extra attention the product probably attracts more people than usually. Sanders relates this to the launch of the co-created Pickwick Dutch Tea blend, which is sold much more than their other line-extensions within tea blends. “Perhaps not just because of the co-creation process, but also because of the buzz that resulted from the enthusiasm within Sara Lee and among the consumers that participated in developing the blend,” Sanders notes. The co-creation aspect was emphasized in the advertising campaign around the Pickwick ‘Dutch Blend.’ “We referred to the co-creators on the packaging and in the advertising campaign,” Sanders says.

“Co-creation can be used to draw extra attention to a product introduction,” Sanders says. Due to this extra attention the product probably attracts more people than usually. Sanders relates this to the launch of the co-created Pickwick Dutch Tea blend, which is sold much more than their other line-extensions within tea blends. “Perhaps not just because of the co-creation process, but also because of the buzz that resulted from the enthusiasm within Sara Lee and among the consumers that participated in developing the blend,” Sanders notes. The co-creation aspect was emphasized in the advertising campaign around the Pickwick ‘Dutch Blend.’ “We referred to the co-creators on the packaging and in the advertising campaign,” Sanders says.

Blankert discusses the results of the ‘Maak de Smaak’ campaign, which had significantly higher scores on brand loyalty and brand activation aspects than other campaigns. There were 311,000 unique participants, twice as much as PepsiCo’s estimated beforehand. Blankert: “The three final flavors were available for only two months and the Lay’s team expected sales of about 2 million bags. However, the final sales number was 6 million.” The Lay’s team was quite overwhelmed by the success and buzz around the campaign. “The success is probably due to the involvement of consumers,” Blankert says, “the flavors were invented by the consumers themselves and the winning flavor was also chosen by them.” The successful ‘Maak de Smaak’ campaign inspired PepsiCo to set up a new team that completely focuses on consumer engagement.

Critical notes

Priester notes that it is not always necessary to involve consumers in order to create relevant products. A firm can also successfully apply the principle of co-creation and consumer-centric thinking, he argues. “Take Apple as an example; their innovation is fairly closed, but they have extremely good client-centered designers.”

Van Kesteren also supports this view: “A good marketer should be able to place themselves in the consumers’ position and imagine what their needs and wants are.” He argues that a co-created product therefore doesn’t have to be any better or more relevant than products developed mostly by a company.

III Visions on success factors

The co-creation process

Several success factors were mentioned by the participants, such as the need for good project management and effective and constant interaction with the co-creative consumers. It is considered very important that these consumers receive quality feedback, inspiration and encouragement. Participants also stress the importance of adapting business processes to facilitate co-creation; they should become more flexible and able to quickly follow through on outcomes. To achieve this, co-creation should be recognized and supported by the whole firm.

Priester: “firms need to open up to new ideas, dare to let go of control, dare to enter new markets and diverge from old ways of thinking an doing.”

Reijnders argues for developing new disciplines within firms, as co-creation and working with online communities require certain management skills.

“Once you open the doors to co-creation, it is difficult to close them,” De Laat explains, “It often brings about an online discussion that continues after a project ends.”

Transparency and consistency in behavior is underlined. Firms should show what happens to the co-creation results and how they are implemented by the firm. “This creates a willingness among consumers to collaborate and share ideas with the firm,” Priester says.

De Ruyck: “Firms should explain and demonstrate what co-creation comprises and how it was executed.” This makes the co-creation claim legitimate and easier for consumers to trust, De Ruyck argues.

Involving the right consumers

Another important factor that influences success is carefully identifying and involving the right people to co-create with. Deciding which consumers to involve depends on the type of task and required skills and expertise. De Ruyck: “We shouldn’t underestimate the average consumers’ innovation competence, but also definitely not overestimate it.” He argues that complex and technical tasks should be allocated to the more technically able consumers. Reijnders agrees that deciding who to involve should depend on the question at hand. He refers to the HEMA design contest as an example. This contest is purely aimed at design academy students, since HEMA considers them to be the appropriate participants for this creative task.

Participants agree that for intensive collaborations, firms should focus on lead-users, who are highly involved and knowledgeable about a product category or brand. According to De Ruyck they can be subdivided into ‘influentials’ and ‘innovators.’ The innovators are always on the lookout for the latest trends and want to try out new products immediately, while the the influentials are more communicative and take into account the needs of others. “Therefore the influentials are often involved in other people’s decisions,” according to De Ruyck.

De Laat foresees a future challenge when it comes to attracting co-creative consumers or designers. “The more co-creation initiatives, the more challenging it becomes to get people enthousiastic about participating and keep them actively involved,” De Laat explains.

Dilemma: intensive VS mass collaboration

Van Kesteren offers some critical remarks on selecting only innovative and creative consumers. He argues that in doing so firms are not collaborating with a representative cross-section of their target group.

Gebauer also stresses the importance of finding a balance: “involving lead-users is very important, but average users are also valuable for giving critical feedback and evaluating the work of others.”

According to Sanders, it is important to find the right balance in order to create added value. The benefit of involving many consumers, e.g. via a cross-media campaign, is that it creates a buzz and raises awareness of the product. Involving a smaller selection of consumers allows for a more intensive and close collaboration, but requires more advertising effort during the product launch.

“You need to foster a strong commitment and manage the project well; this is best achieved by co-creating with a restricted group,” Sanders argues. “However, you need to be cautious not to involve too few people, because then you miss out on important insights,” he adds.

Blankert notes that co-creation is really difficult to pursue through a big or nationwide project such as the Maak de Smaak campaign. He considers the project to be more ‘crowdsourcing’ than co-creation, since intensive consumer interaction and collaboration was limited. “What you actually want (in co-creation) is to involve the consumers that are closest to your brand, the most loyal fans,” Blankert argues. These consumers are very involved and are intrinsically motivated to contribute something to the brand.

IV Challenges and misunderstandings

Expectations

The general opinion is that firms as well as consumers should have a clear idea of the purpose of the co-creation (is it aimed at e.g. a radical innovation, a line extension, or a new packaging?). This helps to manage expectations and to prevent disappointment. Some participants mention that consumers are much more able to react on something innovative, than to come up with it and identify latent needs (Priester, Sanders, Van Kesteren, De Ruyck). Van Kesteren therefore considers co-creation mainly as a market research tool as opposed to an innovation tool: “I consider the added value to be especially in consumer feedback, which can be used to optimize processes and products.” Firms are thus considered to have an important role in unraveling latent needs and in this sense ‘help’ consumers innovate.

Attitude change

All participants address the challenge for firms to conform their whole attitude and behaviour to co-creation and open innovation. De Ruyck notes that firms’ hesitance to implement co-creation, is also partly caused by a lack of evidence to convince managers about the benefits and effects. Furthermore employees may fear losing control over their jobs because consumers are ‘taking over’, and this can make them reluctant to incorporate co-creation (De Ruyck, Sanders).

Blankert also points out that it requires quite a lot of internal discussions and meetings to really change attitudes or processes towards co-creation. Authentic involvement from the firm is considered a crucial factor, because the focus should be on interaction and constructive collaboration. Priester: “This requires a paradigm shift; firms should become creative from the inside out, instead of towards the outside.” He says that it will not work if firms are active in social media, but are not embracing open-network innovation and learning from others. Consumers will not take the efforts seriously.

Gebauer argues: “This means working hard to change the ‘not invented here’ attitude, where ideas coming from outside of the firm are hard to accept and to adopt.”

Reijnders notes co-creation doesn’t imply completely letting go of control and management; “Firms should prepare the process well, determine objectives, use the right tools and involve the right target group,” he explains, “directing and managing the process is crucial.” Reijnders illustrates this with an example of a housing project, where future home owners could co-create a new neighborhood. The co-creation platform was not managed properly and a lot of information and ideas were submitted by a great variety of people, “but there was no constructive discussion among the target group,” Reijnders explains.

De Laat underlines this and argues that firms should not just ‘drop a question’, and then wait for a useful discussion to arise, but they should be reactive and feed the discussion. Managing online communities requires constant attention and feedback and firms should also be prepared to deal with negative responses.

Setting objectives

De Laat addresses the challenge for firms to formulate a concrete goal for the co-creation project. “Firms often don’t exactly know yet what to expect from co-creation and which target group they should involve,” De Laat explains. She says that most often firms want to gain insights, but also have marketing objectives in mind.

Gebauer notes that co-creation can result in concepts and ideas that firms didn’t foresee beforehand. “Product ideas have to fit within a certain price range, planning and distribution channel. If the co-creation output does not fit into this plan, managers might not want to accept this output as a valuable resource,” he argues. Firms should thus become more flexible and adaptive in their planning and development process.

Insecurity

Reijnders notes that firms should be aware that co-creation doesn’t ‘produce’ ready-made products, but mainly ideas and concepts. He also notes that co-creation is not a fixed process and firms should experiment and try new things to find out what is most effective. “What works today, might not work tomorrow,” Reijnders notes, “firms have to remain constantly alert because markets and technologies change quickly.” This insecurity is also underlined by Blankert, since the Maak de Smaak campaign offered consumers a lot of freedom. It was difficult to estimate how many people were going to submit their ideas and the Lay’s team had no idea of the flavours consumers would come up with. Blankert: “This was risky, because we didn’t know whether our R&D department could transform the submitted ideas into actual tasty products.” Partly for this reason, the selection of finalists was done by a jury of experts from different fields (including one consumer). This helped to ensure that only the most promising and tasty products would make it to the finale. The online aspect of the campaign also caused some concern: “the submissions were directly visible to everybody via a live stream,” Blankert says.

For the Maak de Smaak campaign it was not possible to filter submissions first to completely rule out rude or offensive messages. “We built in a filter for swear words,” Blankert explains, “but even then you can not completely rule out abuse, so we had to let go of some level of control.”

Consumer-related challenges

The general opinion is that consumers are quite understanding and flexible. They realize there are restrictions to their influence and boundaries to a firm’s possibilities in innovation. Van Kesteren: “My experience is that consumers realize that not everything is possible and ideas have to be in line with the company’s management.” Participants acknowledge that consumers at least expect recognition, as a sort of reward, for the effort and time they invested in co-creation. Priester warns: “They might expect their ideas to be implemented directly.” For this reason he considers it very important to keep consumers informed about progress and ‘next steps’ after the initial co-creation project is completed.

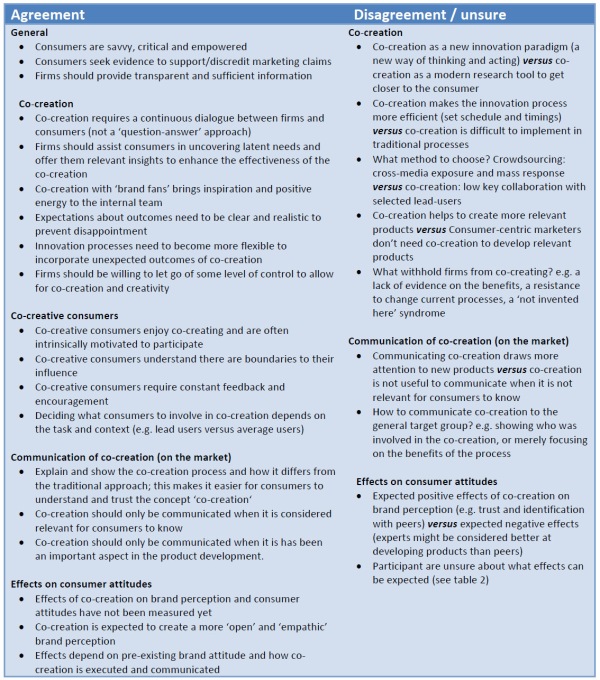

V Summarized overview

The table below offers a summarized overview of the aspects on which respondents seem to agree on, versus aspects on which they have different views or of which they were unsure. (click on the table to get a sharp and enlarged version)

Trackbacks

- Co-creation vs. Crowdsourcing « joycediscovers

- Praktijkvisies op cocreatie - Frankwatching

- Links van de week door Harm Olde – 2011 week 23 | Engaging Times NL

- Smartees @ Insites « joycediscovers

- Pre-test results! « joycediscovers

- Negative side-effects of co-creation « joycediscovers

- Observation before co-creation « joycediscovers

I am surprised at the apparent consensus with interviewed experts about consumers not being able to provide revolutionary, radical, or novel ideas. There is ample empirical evidence that consumers are very well able to trigger radical innovations. Whether they are lead users (see work of Eric von Hippel) or ordinary consumers (see work from Magnusson and Kristensson).

There is also empirical evidence that a large part of contemporary innovations are initiated and developed by users (or consumers). Von Hippel has done many research on this phenomenon, depicted in his two books: The Sources of Innovation (1988), and Democratizing Innovation (2005). Examples: mountain bike, kite surfing, electronic microscope, kayak rodeo, etc.

Hi Marcel,

Thanks a lot for your comment. As you can read in my literature review (see webpage ‘Paper‘), I actually also refer to sources that underline the innovative capacities and influence of consumers (incl Von Hippel and Kristensson).

When it comes to the interviews, I do refer you to the whole document, where you can see that 3 practitioners mentions this (out of 8). These comments are related to the difficulty for consumers to identify latent needs on their own, and the idea that it more easy to react on something than to come up with it. They consider firms to have an important role in unraveling these latent needs and in this sense ‘help’ consumers innovate.

Furthermore, as you can read, some other participants disagree and consider consumers to be very useful resources for innovation.

Kind regards, Joyce